Blog Categories:

- Alan M. Clark

- Alan M. Clark's Writing

- Guest Bloggers

- IFD Publishing Announcements

- Lisa Snellings

- Mark Roland

Of Mentors, Blood Drives and Belly Dancers

From time to time I write short recollections of my life and times. I call these Brief Histories. This is one.

I began attending Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions in the early 70s. They were brought to my awareness by my friend Larry Todd, an artist who worked in that field, as well as in Underground Comics. I was still an art student at City College of San Francisco, involved in political protests against the Viet Nam War and working on the campus alternative paper, The Free Critic. As an artist I was frustrated with academic tracks that had been proposed to me, fine or commercial art, and found Larry’s world much more compelling. He introduced me to works by writers like H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and art by contemporary book jacket artists, magazine illustrators, and comic book creators.

At this time the Bay Area was ground zero for underground comics, and while there were different contingents, most of the artists socialized at parties and book release events. Larry Todd, often identified with his Dr. Atomic character, was enthusiastic about the old EC comics, and their artists like Wally Wood and Jack Davis. He was also a fan of the emerging Philippino comic book artists like Alex Nino and Alfredo Alcala. From his days in New York he knew artists like Bernie Wrightson and Michael Kaluta, who were then breaking into the mainstream. With his close friend Vaughn Bode, he collaborated on magazine covers for Galaxy and If. I would sit, talk and watch Larry as he drew comics or painted in oil. Every visit was a tutorial. Long into the night, he held forth with stories written in his head—but not on paper—historical facts and colorful anecdotes, all while he inked a strip. By 1976, we were sharing a house in Oakland, CA, where my education continued.

Science Fiction Conventions were held in hotels or motels; many still are. My first was a regional conference, Westercon, held in a downtown San Francisco hotel. At this point in time, Science Fiction literature and comic book characters were not the source of major film franchises. It took “Star Wars” to turn the tide and fully transform our niche world of fiction and art into a mass market product. Certainly, we were not pure altruists. No one objected to getting rich, or earning enough to make their living as a writer or artist. At the conventions, in hallways or conference room events, publishers and editors were cornered by ambitious writers or writers to be, eager to pitch a project. Artists gladly directed potential buyers to their displays in the art show, or tried to get assignments from art directors. The activity of commerce was not yet weaponized, being just part of the mosaic of events, readings, discussions and parties.

Being able to meet writers or artists you admired was a cherished part of the experience. In this era, I was fortunate to meet Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber, Frank Herbert, Roger Zelazny, C.L. Moore and George Clayton Johnson to name a few. Of course, if you were not an avid reader, you might be standing next to a major author and not know who they were or what they had written. It is difficult not to think about missed opportunities in retrospect.

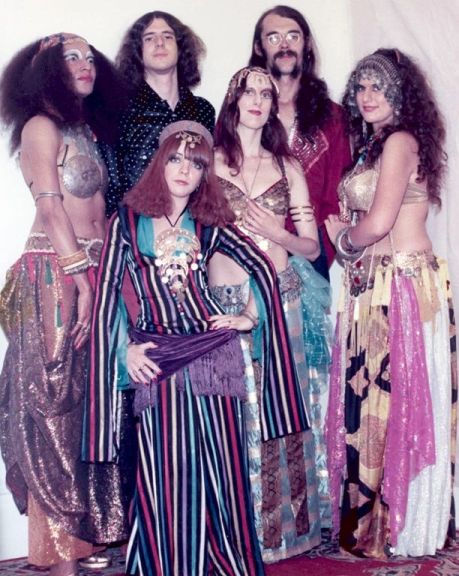

Attendance at the conventions was not limited to hardcore literary types by any means. This was gathering of various tribes: the filkers (singers and musicians,) The Society for Creative Anachronism, the pagans, the gay community, the costumers, etc. Usually these groups overlapped and flowed between each other. This cross-pollination of cultural outsiders created much of the magic. The atmosphere that prevailed encouraged a general openness to trying new things. When I found myself playing drums and flutes for a group of Middle Eastern dancers, it wasn’t so out of the ordinary. Now I was also a performer, though obviously the dancers were the focus of attention. Larry’s girlfriend, Pepper, was the leader of the troupe, and we soon were appearing at Science Fiction and Comic Book Conventions. as well as other gigs. I pursued my art career, and still found time to make rehearsals, practice complex rhythms on the doumbek, and accompany the dancers as they danced in line formation and took their solos.

Robert Heinlein was a guest at the upcoming convention in Santa Rosa, CA, OctoCon, in 1977 or 78. I had read Stranger in a Strange Land in my early teens, and for me it fused the countercultural zeitgeist with fantasy literature successfully. I was not so familiar with his classic SF novels, but had an impression that they were not for me, which counts as another missed opportunity. After Viet Nam, titles like Starship Troopers were less attractive in the anti-military tenor of the liberal Bay Area. There was also much informed criticism of the sexist and racist attitudes prevalent in much pulp era Science Fiction. The new wave of writers like Samuel Delany, Ursula Le Guin and Roger Zelazny were lionized justifiably, while some of the major figures of the past were believed to be out of touch.

In his later years, Heinlein survived a life-threatening emergency that required numerous blood transfusions. After recovering, he became a fervent advocate of citizens donating blood as well as the importance of blood banks. In keeping with this cause, all of his convention appearances at this time included a blood drive. Since our troupe was planning to attend this convention, Larry arranged for our troupe to perform at Heinlein’s blood drive.

We rehearsed and brought our current line-up to Octocon at the laid-back Red Lion Inn. Pepper was the leader and driving force of the troupe. The other dancers and musicians constituted satellites attracted by her gravity. She demanded a serious commitment of the members, insisted they take lessons and make their own costumes. Some stayed and improved, others drifted away to other pursuits or other troupes. Larry was not a musician, but helped with equipment, and making signs and props. Another member of our social circle, artist John Burnham, was also playing drums with me at this time.

In our exuberance and poverty, we slept on the floors of packed motel rooms to divide the cost of attending conventions. In the back of my mind, I hoped I would make sales in the art show and turn a profit for the weekend. Playing with the troupe always presented a certain degree of drama; the possibility of the performance being sloppy, tensions and rivalries between the members reaching a boiling point. Fortune, or perhaps the availability of high-quality intoxicants, smiled that day. We played near the swimming pool, in front of the suite of rooms that were the site of the blood drive. Pepper danced with a sword, Melissa with a boa constrictor, and Molly with a reed cane. When we were in the groove, the music and rhythms were hypnotic, the finger cymbals of the dancers answering the drums, the ululations and exclamations of the dancers encouraged each other. The dancers took the stage and engaged the audience with the movements of the dance, a deep ritual of primal earth religion, beneath the veils of sequins and bright fabric. Pepper’s troupe combined authentic Egyptian dances and costumes with the more theatrical western, or cabaret style.

The band gathered a good crowd by the conclusion of our set, and then the blood drive volunteers encouraged donations or else a commitment to donate from the audience. The willing were brought into the suite to give blood, have refreshments and schmooze with the dancers. Signed copies of Heinlein books were provided as an enticement, as well as meeting the noted author.

From the bright sunshine of the pool, we entered the suite, dressed in flowing garments, still on an adrenaline rush, post-performance. One by one Larry introduced us to Robert. I remember Heinlein being extremely gracious, and he thanked us for our participation. His eyes were bright and he smiled broadly. I could not ignore that his skin was ashen and handshake firm, but icy. He seemed completely at ease with our band of long-haired artists and eccentrics, as well with some of our practices, like open relationships.

Heinlein was a complex figure. It seemed incongruous to me that someone associated with the military, and who expressed a xenophobic suspicion of alien races in his writing, would be so nonjudgemental, an advocate of non-conformism. But this was a long-term theme of his work as well; a healthily distrust of the establishment, and support for the rights of individuals. Due to the freewheeling nature of the time, I had the honor of meeting him, and to briefly grok the presence of a generous, visionary man. In his writing he envisioned—often correctly—how technology would change our world. To his credit he also fought to preserve the lives of others; normals, water brothers and sisters alike, through the communal act of donating blood.

—Mark Roland

Eugene, Oregon